“It’s a weird vibe in here,” I say, looking out across the empty bar.“

It’s the End,” my brother Alex replies. “That’s what the vibe is. The End.

”We’ve come to the edge of Chicago, the outskirts of Midway Airport, to the only bar anyone could think to send us to. The only other patron here left as soon as the Cubs game ended. Now there’s just the soft glow of haphazardly strung Christmas lights and neon beer signs. There is no music playing. This is Karolinka’s, the last place in Chicago, we were told, were there might be polka.

For a couple of years now, my brother has talked about the polka bars in Chicago. Every time I’ve come here, he’s asked me to seek them out. Whenever either of us talk to anyone from Chicago, we ask if there are still polka bars. “None that I can think of,” everyone says. “Maybe when I was a kid,” they say. In 2022, a friend who’d lived here her whole life eventually came up with Karolinka’s. “That’s your best bet.

”So finally we decided to meet in Chicago and see what we could find. And we’ve, at last, come to Karolinka’s. Neither of us expected to fling open the door to a some rollicking polka party. But I expected, I guess, something more than this.

Maybe 15 years ago, Alex was talking to his friend Joe about the kind of music that he listened to growing up in Omaha. “My mom,” Joe told him, “listened to polka.” Up until that moment, Alex hadn’t really considered polka—not as anything more than as a punchline, a cheap joke about midwestern culture.

Alex is three years older than me, and he’s the source of most of my music taste growing up. His entire life has been a relentless quest for new and interesting music. Intrigued, he began listening to polka. What was the deal? How popular was it? Why was it popular at all? And where had it gone? “It was the only music that didn’t make any sense to me,” he told me. I’ve ordered us shot of Malört, which we attempt to suffer down. “Where was it? There’s got to be edgy polka. Where is the Eddie van Halen of polka?”

What if it was there, but somehow just out of sight? Many of us, in one way or another, want to believe in an underworld, a hidden world out there, closed to all but chosen insiders and the very lucky. A world that can only be accessed by freak chance or dedicated seeking. Music in particular generates this kind of longing—that need to have seen the next great band in some dingy club before they were big, the search for the word-of-mouth rave in some nondescript warehouse building. Why couldn’t polka have this too? The secret fire, the subterranean network? A polka underground?

Alex began looking for it, some secret continuing legacy of a vanishing American art form. He started digging up weird stuff on Spotify, hunting down things in record bins. At some point he came across a song by Eddie Blazonczyk and the Versatones from 1990, “Polka Lounges in Chicago.” “Try to remember where you used to go,” Blazonczyk sings, “to the polka lounges throughout Chicago, Close your eyes a while, daydream with a smile, We’re going back to days gone by to stop and just say hi.” Aside from the chorus, the song is nothing but a litany of bars, dancehalls and social clubs: “Midnight Inn and Sophie’s Dollhouse, 505 and Leon’s Tap, Wally’s Last Stop, Butterball’s, Vy’s Hideout, and the Old Mouse Trap,” he sings, the words coming so fast it’s hard sometimes to make out every name. He sings of Lucy’s Wisconsin Rendezvous, of Club Antionette and the Lonely Hearts, Korosa’s Baby Doll and the Dew Drop Inn. All these places that once must have existed. Surely something of this must remain?

All that’s left of this smorgasbord is Karolinka’s, originally known as the Baby Doll Club, founded by polka legend Eddie Korosa. Born on the southwest side of Chicago, Korosa began playing the accordion when he was six years old; by the time he was a teenager he was already playing in bars with his band, The Merry Makers. His hit, “The Baby Doll Polka,” released in 1951 made him a name, and he opened up the club three years later.

Eddie Korosa, they’ll tell you, was a legend. Polka in Chicago wouldn’t have been the same without him. Everyone has great memories of him, dancing on the bar as he played the squeezebox, the consummate entertainer. His status as a Chicago icon translated into a long-running show on WCIU, “Eddie Karosa’s Polka Party,” where viewers could tune in and watch happy couples move across the floor. (KCIU’s other attempt at a show that consisted of people dancing to music was more successful—launched in 1970, Don Cornelius’s Soul Train was quickly syndicated and took the nation by storm.)

Eddie died in 1998, from liver failure at the age of 80. The Baby Doll had moved by then at least two times, to smaller spaces further out, and Karolinka’s, with its tired ambience, holds little remnant of his energy, at least not tonight. But it’s all we’ve got; otherwise, it’s been a largely fruitless search. Every other bar from Blazonczyk’s song seems long gone, including Club Antoinette, which was owned by Eddie’s parents and is now a taqueria. We’ve run down this city, going in circles and turning up nothing. Chicago is home to the International Polka Association, which has a museum on the South Side, but it doesn’t hold regular hours and you have to call a number on the website if you want to visit it. Alex calls and leaves a message.

It’s a strange thing, to be in a city so full of bustling life, and to be looking for something which doesn’t seem to exist. Like suddenly this same city feels wasted and used up. Chicago is alive to everything but the thing we are looking for.

But the thing about searching for an underground is that it’s impossible to prove it’s not there. Perhaps we’re just not ready for it, we haven’t proven ourselves worthy. Secrets, after all, are meant to be kept.

***

What is it about polka that makes it so cringe now? When polka was first invented in the nineteenth century, it was radical: fast-paced, portable, and, above all, it was sexual. Driven by the accordion, a newly invented instrument that obviated a need for an orchestra, polka could be played in small bars and basement clubs. But more importantly, dancers held fast to each other, men and women pressing their bodies against one another as they careened across the floor. It was hot and sweaty, exuberant and excessive.

By the time it got to the United States in the twentieth century, it was different. In Poland, polka is considered a music invented and played by Czechs, but in America, it became the music of Polonia—the Polish-American community. Cultural studies critic Ann Hetzel Gunkel has argued that a “dual identity—Polish and American—is central” to polka, she writes. She describes polka as a underground force, an art form that resists the demands of assimilation, and creates instead a “kind of border identity.” To assess polka, she writes, “in terms of the aesthetics of mainstream music or mainstream literature is to miss the point entirely. A refusal of those aesthetics as normative is part of the counter-cultural nature of ethnic articulation.” Charles Keil, Dick Blau, and Angeliki V. Keil, in their book Polka Happiness, argue similarly that polka represents “at least a hundred years of resistance to the melting pot, a refusal to disappear into mediated entertainment, a ‘no’ to monoculture, and an ongoing vernacular alternative to the sorts of fun manufactured by the culture industry.”

This refusal to assimilate may be part of what began to doom polka in the eyes of the public: The music of a hyphenated identity, it could never thrive outside Polonia, and as later generations of Polish-Americans moved out of ethnic neighborhoods and increasingly saw themselves as just Americans, then they could not take polka with them.

Polka refused to assimilate, and the world left it behind. Listening to the incessant, bouncy tempo and frenetic accordion in Blazonczyk’s song may make it hard at first to notice the longing embedded in these lyrics. It runs through a lot of polka from the 90s, including Lenny Gomulka’s 1991 “Where Were You Back Then Polka” (“Where were you when Wally wished that he was single, Where were you when Lush sang, ‘Hey Cavalier’? Where were you when all the Brass ‘Rolled Out the Barrel,’ And Ray Henry played his ‘Ballroom’ far and near?”). It’s hard to see in such sentiment the kind of counter-hegemonic practices that Gunkel suggests they might have. To me it all sounds poisoned by nostalgia, and a dead-end fealty to the past.

***

Where was the Eddie van Halen of polka? “He wasn’t there,” Alex says as we sit in Karolinka’s. “Eddie Blazonczyk was the only one who even played in a minor key.” We’ve moved from Malört to the only beer on tap, a nearly undrinkable Polish pilsner I’ve never heard of. “They wanted it to stay the same, so they kept it that way. And that’s not how you keep an art form alive.”

In any given genre of music, you can think of the innovators—the ones who broke the form wide open. But the thing about polka, is that no one ever took it as an art form unto itself, an end unto itself. It was always a means—a means to community, a means to identity, and a means to having a great time, a reason to get out of your chair and dance.

Eddie Blazonczyk put out more than 60 albums, but scanning his discography, the titles tell a story of endless repetition: Polka Parade (1963), Happy Polka Music (1966), Polkas A Plenty (1969), Polka Jamboree (1976), Roaring Polka (1978), Polka Cruise (1980), Everybody Polka (1990). The music, like the titles, never really goes anywhere—but then, that’s the point. It’s only purpose is to take you in circles around the dancefloor.

Alex’s friend Dan wrote to him about growing up in that environment, and how he came to hate polka because it was “just so non-negotiable. The city I grew up in was exceptionally diverse for the time/place, but the Polish folks felt like they were at war with new immigrant families from the middle east and Puerto Rico…. I just felt super lonely among ‘our people,’” who were “largely just drunk older dudes and inaccessible entertainment.”

Meanwhile, I realize, Alex and I have also been trying too hard to keep a thing alive: a belief in a hidden world that could still be out there. A polka underground. I realize now that when he first told me about it, I could’ve spent an hour or two researching it and making a few inquiries and figured out soon enough there was nothing there. But I clung to the idea—this little bit of weird wonder, something we spent years talking about, something that’s led us in circles until, finally, we’re here: a dead-end bar with terrible beer.

Another woman has come in. She orders in Polish. The bartender pours her the same beer we’re drinking but adds a pump of raspberry syrup, which apparently is the trick to make it palatable, a trick everyone but us already knows. Eventually we start talking to her: she’s from Warsaw, having moved here twenty years ago to be with her son and grandchild. But the neighborhood has changed, she mutters, and when I ask her what she means, she says there’s too many Mexicans.

***

The next day the guy from the International Polka Association calls back. The museum has lost its lease. He doesn’t know when they’ll have another location, if ever. “It’s a generational thing,” he says. He’s 59 years old, and he’s one of the youngest people on the board. “People are dying off,” he says.

If you’re interested in polka, he says, try Minneapolis. Or Wisconsin; there’s still polka happening in Wisconsin. Or Pittsburgh. Or Buffalo. It’s still out there, he’s telling us through the defeat in his voice, for the dedicated, for the seekers.

Colin Dickey is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, and, most recently, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy. He divides his time between Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

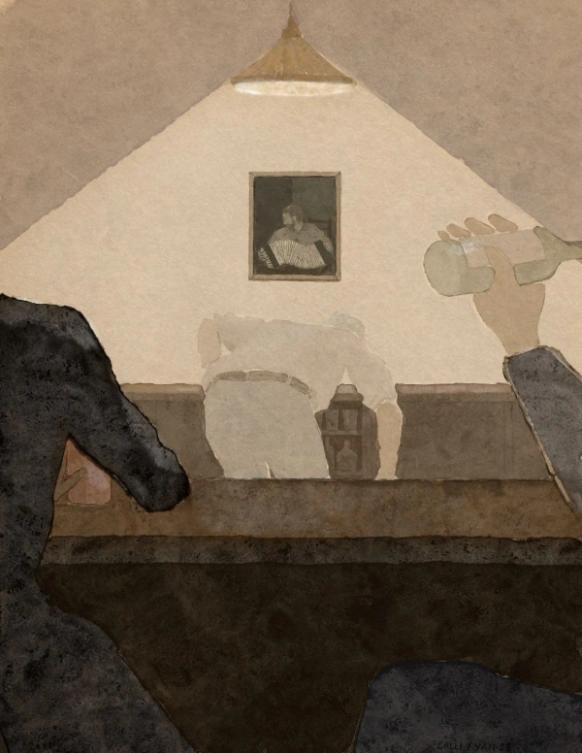

Art by Calli Ryan