Colorado Springs is decidedly not My Kind of Town, but the Broadmoor Hotel is my kind of hotel: Antiquarian, rambling, in the tradition of The Shining. There’s an ominous air—George W. Bush decided to give up drinking after a night of relentless boozing there. These days, it is the annual home of the Space Symposium, a conference where you might unveil a new rocket, or make a hand-shake deal for satellite imagery of terrorist training camps. The best panels are classified, and the dark, wood-paneled hotel bar is teeming with military officers in uniform, and an assortment of dark-suit-white-shirt-red-tie guys from various intelligence agencies, space bureaucracies, and defense contractors.

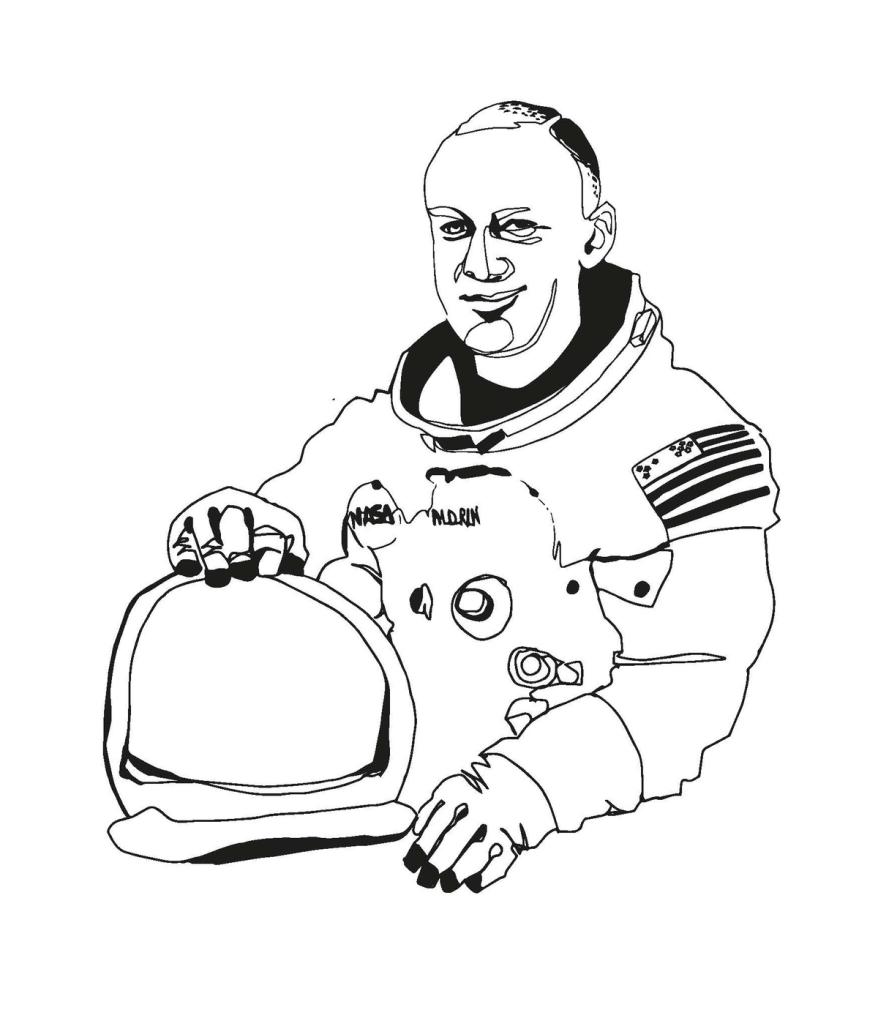

And then Buzz Aldrin and his entourage arrive; his entourage mainly blousy middle-aged women, befitting an octogenarian space hero. Buzz, who you may recall as the second human to step on the Moon back in 1969, is wearing a silver lamé blazer covered with colorful mission patches and an American flag tie. At this time, a year ahead of the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing, Buzz is alive and ubiquitous at space-related events. You would be, too, if you had been to the moon and wanted to hang out with people who think that’s awesome. He’s selling custom t-shirts that he often wears with red, white and blue suspenders.

Watching Buzz (it just doesn’t seem right to refer to him as "Aldrin”) riding high and shaking hands, working the room, it occurs that he’s been doing some version of this, wherever he goes, since 1969. What does that do to your brain? At 93, Buzz is one of four people alive who have walked on the Moon. The other three are Not Famous: an alleged serial grifter, a born-again Christian, and a right-wing anti-China hawk. Buzz is the original, emerging from the same Cold War fighter pilot milieu as the rest of the classic astronauts like a wildflower blooming in a midden.

The model astronaut is your John Glenn or Neil Armstrong: Laconic, unruffled, square-jawed. Buzz can do a good impression of these qualities, but he was a different drink: Armstrong’s legendary quote is “one giant leap for mankind”; Buzz’s entry in the ledger came when he promised ground control he’d “let you know if I stop breathing” when a medical sensor malfunctioned. He was not trained as an envelope-pushing test pilot like the other early astronauts, though he shot down two enemy aircraft as a fighter pilot during the Korean War. He was the first astronaut with a doctorate—his colleagues called him Dr. Rendezvous because he wrote a dissertation on tricky meet-ups in space. He was the second man to walk on the moon, but in his telling, the first to urinate there. Pixar didn’t call their cartoon space hero “Neil.”

Buzz’s version of the space program ended more quickly than anyone involved imagined, killed by the victory of landing on the Moon and the costly defeats in Vietnam. He became an astronaut in 1963, he retired in 1971. How do you follow up on that? Struggle, mainly, with booze and women and depression. His therapist had him try selling used cars for a while there, in an effort to find some semblance of a normal life. (Imagine seeing him on the lot, asking permission from his boss to give you the friends and family price.) Buzz eventually quit drinking and settled into the lane of freelance space nostalgist and visionary, helping make books and movies about his space program while advocating expeditions to Mars. He has appeared on Dancing With the Stars, The Big Bang Theory, and Hell’s Kitchen.

II.

In 2002, Buzz returned to the public spotlight in a violent version of the Marshall McLuhan scene in Annie Hall . Badgered by a conspiracy theorist named Bart Sibrel, who accused him of lying about the Moon landing, 72 year-old Buzz uncorked a stiff right in his face: You know nothing of my work. This moment, which you can see from a poor angle on YouTube, sticks with me; I thought about it often during the trend of famous athletes like Kyrie Irving and Steph Curry claiming the earth is flat and the moon landing was faked. This irked me on a pedantic journalist level and as a fan who wanted these cool young athletes to also, like, accept Enlightenment epistemology, but it also turned out to be a warning signal about the fucked-up information environment we live in now. As Irving recently spiraled into full-bore anti-semitism, I wished Buzz had an opportunity to punch him in the face, too.

This meme is unique to being an Apollo astronaut. There are plenty of conspiracy theories about the 1960s, some worth entertaining, but it’s notable that most of the protagonists have passed. Buzz is the rare figure still alive to see his biggest accomplishment become myth, while at the same time seeing it becoming reality again: The US is planning to return people to the Moon later this decade, while billionaires have created new companies that have made going to space cheap enough for other billionaires to cosplay as astronauts on tourist trips to low-earth orbit. The less shameless ones try to figure out a charitable partner, or pay to bring along an ostensibly more deserving passenger.

Which brings us to the wrinkle in the whole astronaut thing: they are symbolic, “spam in a can” as Glenn famously put it. The heroism involved has more to do with accepting the risk of death in space than exerting prowess. The job did require skilled pilotage and quick thinking, but more and more the challenge is following precise instructions under discomfort and not losing your mind spending too much time thinking about the infinite abyss separated from you by six inches of metal assembled by the lowest bidder. Astronauts on board the International Space Station, who make up most of the people in space today, are the world’s most over-qualified mechanics and laboratory technicians.

Much of what people do in space that makes our lives better—GPS navigation, global communications, scientific research—is done best remotely. Human spaceflight is an exercise in raising the bet: This country (or this company) can put a person in one of the worst places anyone can ever go, and bring them back in one piece. Cleaved from the geopolitical significance of the Cold War, sending people to space can seem a bit wasteful; it says something that unlike Glenn, Buzz has declined offers to return to space. The actor William Shatner, flown out of the atmosphere by Jeff Bezos in a 2022 promotional stunt, had a visceral reaction to the experience. His return to Earth gave us the indelible image of a traumatized Captain Kirk explaining to Bezos that space was literally a void of death, while the billionaire struggled to open a bottle of champagne.

And yet: “Astronauts are heroes” is the first sentence of a book, published this year, arguing that robots have made space explorers obsolete. Even the people who want to get rid of astronauts feel the need to praise them. This may be due to gauzy memories of the 1960s or the excellent film-making of Ron Howard, but there is something very human about the attraction to betting your life. This category of activity is dying out: War is decidedly seen as a waste, not a noble art. Most of Earth’s various frontiers have been conquered and exploited. Climbing Mt. Everest is an exercise in risky tourism. Reaching the bottom of the Mariana Trench is tougher, but generally the skill in question is philanthropic networking. Buzz himself was trucked to the North and South Poles at ages 68 and 86, respectively.

We’ve spent a good deal of time and effort, civilization-wise, trying to eliminate death and push it to the margins of society. But the real spin on Buzz’s whole thing is that he conquered death in 1969, and nobody has the language to talk about it, or even a way to do the same thing today.

III.

The year he appeared in the Boadmoor’s bar, Buzz’s children and a former business manager sued him to obtain his power of attorney, alleging that he suffered from dementia and fell in with bad advisors who exploited his name for their own profit. Buzz counter-sued, arguing that his children were slandering him. The two sides settled out of court, seemingly to avoid controversy ahead of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11; few things could be more unsavory than the Lear-like spectacle of children fighting over the spoils of a failing space traveler. (Calls and emails to Buzz, his children, his current and former business partners, and their various attorneys were not returned.)

The day before the Moon landing anniversary, Buzz joined a televised Oval Office news conference to mark the occasion. The head of NASA explained his plans to return to the Moon in the years ahead, and Buzz and Michael Collins, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, were not impressed, and said so. Buzz lectured the increasingly wild-eyed NASA official about why the agency’s plans to go back to the Moon were all wrong, going direct to Mars is the real move. It was arguably rude and his vision outstripped anything Congress would have been willing to pay for, but he didn’t seem demented, or at least more demented than usual. Trump reveled in the chaos, asking his staff “who knows better than these people?”

The last time I saw Buzz in person was later in 2019, at yet another space conference. At a panel on the future lunar economy, Buzz pulled up next to me onboard an elder mobility scooter, accompanied by a female friend, also on an elder scooter. He was a picture of good cheer, though he still preferred to see astronauts aim for Mars. Since the pandemic, he hasn’t been out and about as much, and judging solely by his official Twitter account, it seems associates have taken over the management of public image. Still, it’s Buzz: On Halloween, he posted two images of him in green alien sunglasses and a backwards purple hat, accompanied by a similarly dressed woman and a man in an Alien-cum-Gimp suit mask, while eerie theremin music played in the background.

The comedian Kevin Nealon tells a story about meeting Buzz on a beach in Los Angeles. Nealon asked Buzz if he had ever worried that he would become trapped on the Moon, which was indeed something that NASA was worried about at the time—there was a concern that too-fine lunar soil would swallow up the lander and the astronauts inside as soon as it touched down. Initially prickly and accusing Nealon of being a wise guy, Buzz eventually said he wasn’t worried, he was confident in NASA’s plans to get them home.

But Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Jr., didn’t come home from the Moon; Buzz came home. And one day, inevitably, he will go back.

Tim Fernholz is a writer in Oakland, California. He is a senior reporter for Quartz and the author of Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and the new Space Race.