On the afternoon of September 11, 2001, D.C. cardiologist Dr. Jonathan Reiner was worried about a patient. He was stuck at work––like most in one of the three cities that had been targeted that morning––at George Washington University Hospital. In advance of a house call that evening, Reiner had asked his patient, a 60-year-old father of two, to get a blood test for potassium, a critical nutrient for the functioning of the cardiac muscle. Too high or too low a value can spell disaster. Like a charley horse in the heart––a surplus of potassium is the third ingredient in the cocktail still used in most lethal injection states––the hyperkalemic muscle is liable to seize into arrhythmia and, eventually, cardiac arrest.

Reiner feared such disaster when the lab returned his patient’s result that day: a potassium value of 6.9, high above the healthy 5.2 upper limit. Reiner knew that his patient was potentially walking around with the cardiac equivalent of an unpinned grenade. The patient’s primary care doctor asked Reiner if the implanted cardioverter-defibrillator he’d had installed only three months prior would be enough to stop a deadly arrhythmia. Reiner answered truthfully: no. The problem was, the patient was out of contact. At that moment, the patient was in a tunnel somewhere underneath Washington, D.C., surrounded by Secret Service agents, cabinet secretaries and military personnel, because Vice President Dick Cheney––America’s uber-cardiac patient––was the highest-ranking government official currently on the ground.

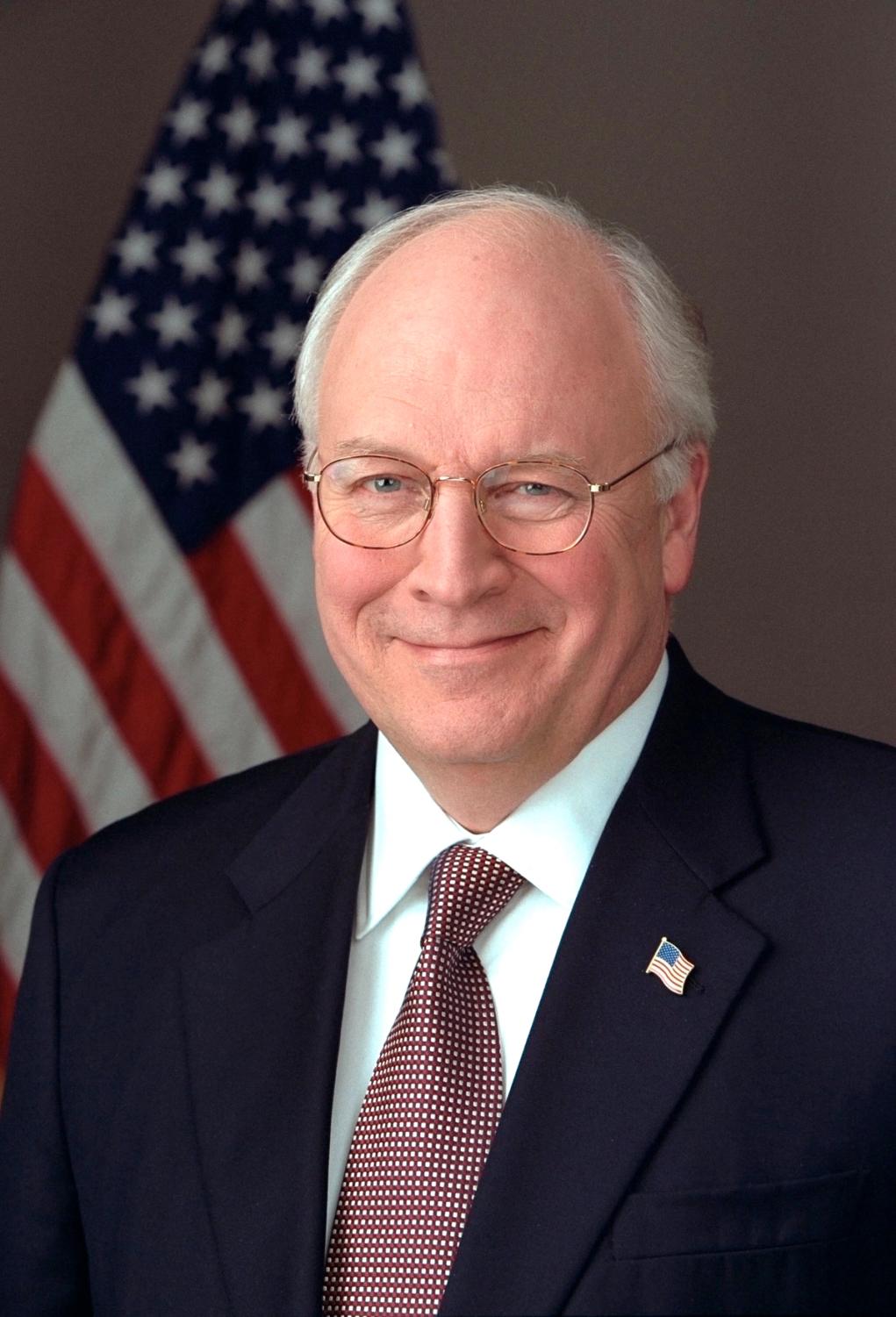

Cheney and Reiner recount this story in their joint 2013 book Heart: An American Medical Odyssey. The doctor had pitched the book to his patient two days after Cheney’s successful heart transplant in 2012 on the premise that Cheney’s chart represented “the entire history of cardiovascular medicine.” In the book, the pair dispense anecdotes concerning Cheney’s health during moments of great political importance. They revel in the drama, unaware of the doubt these stories might engender about Cheney’s time in office. The 9/11 story ends with a hand-wave: when Cheney’s blood was re-tested the next morning, his value had returned to normal. Reiner, along with Cheney’s White House Physician, Lew Hoffman, decide that the “potentially lethal” level must have been a false result owing to “the prolonged delay in processing the sample, which ensued following the evacuation of the White House.” This is not hard science, but educated speculation, which medicine is full of. Potassium levels––especially when managed in heart disease patients––can be fickle, dropping and rising several times over a single day. Given Cheney’s own cardiac history and the fact that he was on potassium supplements at the time, it’s plausible that the result was genuine: Cheney got lucky, and his level quickly reverted to normal the next day. This anecdote, like many others in the book, attempts to humanize Cheney, then reinforce his position of strength––he was still in control. Physical danger becomes a narrative device, the possibility of death only underscoring the achievement of its survival. I suppose it’s easier to conclude that the man “playing a key role in events that have shaped history” (per the book jacket) was not one wrong heartbeat away from catastrophe.

When I first learned I would need a pacemaker at the age of nine, doctors and family told me to look to Cheney––among a list of other aged: cousins, neighbors, friends at my grandmother’s retirement home––as an example of success. A hospital social worker had given me a keychain with a replica pacemaker cast in steel. A similar trinket of wires and algorithm was ticking perfectly in Cheney’s American chest. I measured the weight of the keychain in my palm and thought of the Vice, two tethers to the real urging me not to be afraid. But with every name, I became less interested. These people, even Dick Cheney 21 years ago, were far too old.

Cheney is the American arms state in a man: always creeping toward senescence, swapping ever more of his live components for technological shortcuts, a waste of public funding. He has persisted for decades through the vagaries of cardiac decompensation: five heart attacks, several implanted devices, one sudden cardiac arrest, end-stage heart failure, and four open-heart surgeries including the transplant. Before he finally received a fresh heart in 2012, he spent 20 months on the waitlist––a far longer interval than is endured by most transplanted patients. Reiner points to this detail as evidence that Cheney “never asked for, and never received, any special accommodation while he was on the transplant list.” (Reiner also acknowledges that, at the time, heart transplants were only rarely performed on patients older than 70; Cheney was 71.)

But Cheney’s endurance is inextricable from his time as Vice President. In 2007, Cheney’s physicians got Medtronic to build him a custom ICD without the device’s bluetooth capability on the premise that it made the Vice President prone to hacking by a foreign power. Elsewhere in the book, Reiner describes a tightly choreographed day of multiple scheduled medical tests which he acknowledges was “a perk not typically available to the general public.” And eight years of personal medical detail certainly helped a man with congestive heart failure survive his way to transplant. As he gets older, Cheney joins a club of modern elite figures––inclusive of U.S. secretaries of state and toxifying media moguls––whose deaths we desire as some consolation for the evil they’ve done while breathing. But such figures tend to live long, healthy lives. Aware that they often die of old age, surrounded by beloveds, on high thread-count sheets, we cannot stem the urge to celebrate.

Artist Josh Kline imagined a proximate catharsis in his 2015 video installation, Crying Games. Cheney and other figures of the Bush era are rendered through face substitution software as anguished prisoners sobbing out apologies. The uncanny efforts of the software to appropriately map the faces, the obviousness of the actors’ bodies beneath them, the green screened prison walls, the non-specificity of their words––Kline’s revisionist work elicits disgust more than comfort. The piece emerges from the same liberal eagerness for performative retribution that cohered into its own lexicon under Donald Trump.

Even Cheney participated in that memetic discourse, calling Trump the biggest “threat to our republic” in a 2022 ad for his daughter Liz’s reelection campaign. In June 2020, Liz posted a photo of her father wearing a surgical mask, accompanied by the caption “Dick Cheney says WEAR A MASK. #realmenwearmasks.” At the end of the Bush administration, Cheney had an approval rating as low as 13 percent and a heart that had swelled to “twice normal size” from coronary disease. In the relief of his absence from office, Cheney’s approval has only grown; Trump’s former natsec advisor John Bolton will apparently cast a write-in vote for Cheney this November. And the former Vice President’s cardiologist estimated that his new transplanted heart would give Cheney “a legitimate chance of reaching 80.” Cheney’s new heart revived him twice-over. Once history’s actors are out of power, set back into civil society, they begin their real work: pruning the historical memory. In its own counter-history, Crying Games asks us to consider what consequences could even be feasible, or satisfying, or enough to stop the power of collective revision.

In an interview with 60 Minutes following the release of Heart, Dr. Sanjay Gupta presses Cheney on whether his diminished health affected his ability to do his job. “You were instrumental in many big decisions for the country, including going into Afghanistan and Iraq,” Gupta reminds him. “And [the] terror-surveillance program. And enhanced interrogation,” Cheney counters. Cheney continually deflects Gupta’s invocations of studies linking heart disease to memory loss, impaired cognitive functioning, and depression, saying only, “I was as good as I could be, you know, given the fact that I was 60-some-years-old at that point, and a heart patient.” His cardiologist seems to regard Cheney’s physical survival as a product of the same internal force that compelled him toward high office, while Cheney seeks to disentangle his health from his job. He prefers a stance of humble grit, painting himself as any other patient.

Both of them are right. Cheney’s political career can be seen as an “immortality project,” the pursuit of personal or professional extremes meant to distract oneself from death anxiety, a concept outlined in Ernest Becker’s 1973 book, The Denial of Death. The project Cheney followed, what Becker might have termed one of “destructive heroics,” became particularly useful in delaying his mortality. As for his refusal to acknowledge a correlation, a rejection of conscious thought can be essential to this distraction. If we stop moving, administrating the lives of others, and allow in stray noise, thoughts of our eventual deaths might slip in too. But neither Cheney’s cardiologist nor Gupta are interested in “why.” They are more concerned with “how”: how could one man withstand so many severe, life-threatening medical issues, and all their attendant consequences, all while being the Vice President of the richest country on Earth? The answer is in the question.

Jameson Rich is a writer from Boston, Massachusetts whose work has appeared in The Drift, The New York Times, Wired, Dirt, and more. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York with his sixth pacemaker.