After the science experiments and before the cupcakes, we met the star of my four-year-old’s birthday party, outside in her coop.

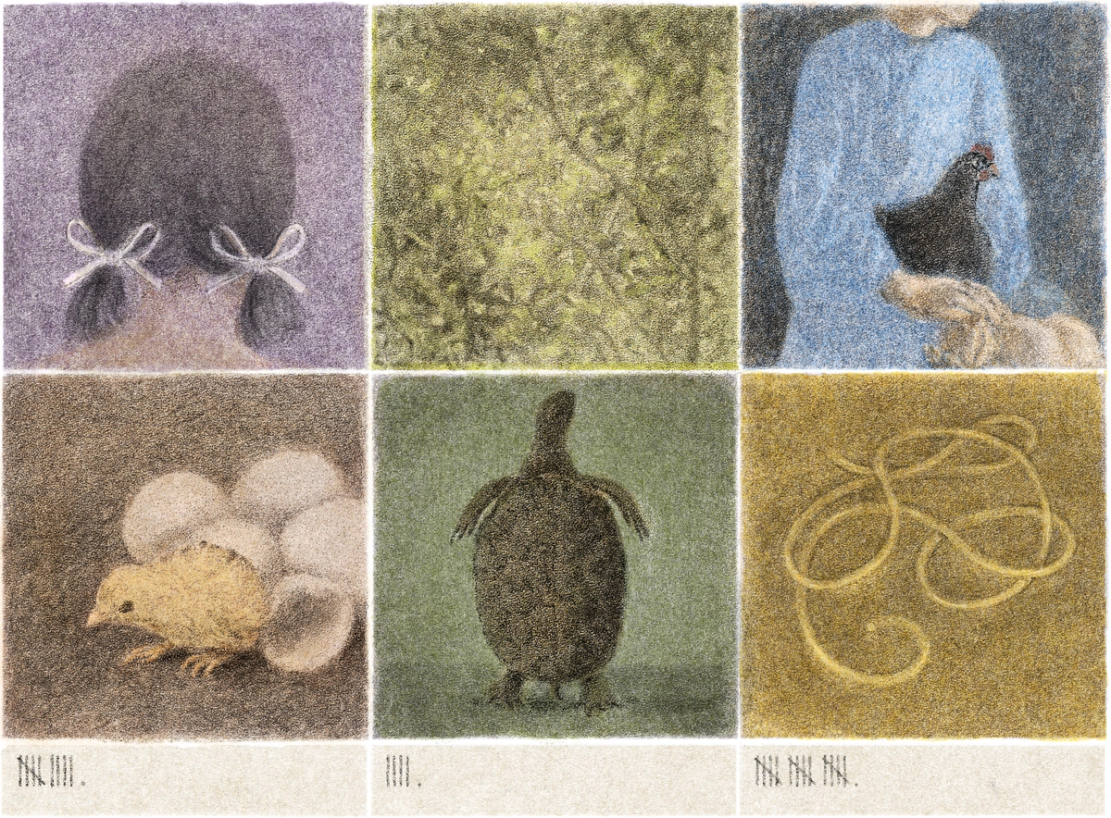

While the chicken strolled from kid to kid, taking dried worms from the Dixie cups in their pudgy hands, Miss Carmen explained, “Spicy Mildred is almost nine years old, which means she’s toward the end of her life.” She was gentle but matter-of-fact—science!—and the kids didn’t seem to hear, but tears pricked my eyes. Inside, we had just seen Spaghetti, a turtle who, at nine years old, is in the beginning of her life. Miss Carmen told me that children invariably pronounce her name “Puh-sketti,” a baby-talk cliche made adorably true, until one day, like a flipped switch, they say it correctly.

Carmen picked up Spicy Mildred and the kids crowded around to pet her. I reached over their heads to touch her for myself—her feathers were softer than I imagined—and flashed back to my youth: In the scrum at a stage door, my fingers brush someone beautiful, someone I love but do not know, as they pass.

Then, like always, it was over too soon, as thrilling for me and inconsequential for her as any celebrity sighting. Spicy Mildred went back to her perch, and I cooed about the moment the rest of the day.

Once, about two years earlier, my daughter started singing over dinner: Spicy Mildred, do do do do, Spicy Mildred, do do do do.

She could talk, she knew words. But I didn’t know that she knew these words, or that she had any reason to put them together. Was this something mistranslated by her toddler brain, or maybe a song she learned at daycare? Who is Mildred? I asked; my daughter giggled and dropped rice on the floor.

I learned later that Spicy Mildred was a chicken at the neighborhood science center her daycare visited. I recognized how important Spicy Mildred must be for her to make up a song about her and still sing it hours later. I’d begun introducing my child to things that I love—Muppets, Carly Rae Jepsen—praying that she would share my enthusiasm. But here was the first thing we could share that she introduced to me. Spicy Mildred was a window into her confusing, post-baby interiority, a voyager from her new, private life. She loved Spicy Mildred, so I loved Spicy Mildred.

In 2020, when one of the two chickens at Kiddie Science passed away, Carmen Castillo-Barrett needed another—living solo is not good for a chicken’s mental health. A friend gave her a mature Black Australorp hen from the same hatch. She was at the bottom of the pecking order, literally. She was one of the last to eat during mealtimes. She didn’t have a name.

When the new hen arrived, the first thing she did was beat up the other chicken, Castillo-Barrett says. She separated them, but the new chicken busted out of her enclosure. She tapped on the window with her beak during classes and laid eggs on the window sill. On the third day, she started vocalizing, a shrill yell that Castillo-Barrett had never heard from another chicken.

To teach the new chicken to use the nesting box, Castillo-Barrett had to lock her in, 30 minutes at a time. The hen screamed and banged her head against the wall. As Castillo-Barrett tells me this, I’m reminded of sleep training my baby, of her wailing and thrashing at the crib rails. “But she was happy, she was healthy, she was fine,” Castillo-Barret says about the chicken. “She just wanted to do what she wanted to do.”

The new hen needed a name. Kiddie Science classes—kids from two to 10—voted, and when Spicy and Mildred came to a tie, Castillo-Barrett decided to combine them. “Spicy” turned out to be especially apt.

In the time that followed, Castillo-Barrett got more chicks to act as a buffer around Spicy Mildred. Castillo-Barrett built a bigger, more secure enclosure. Spicy Mildred has taken nearly half of it as her own, separated by a long branch, and if another chicken enters her space she will chase her away. She steals the worms that other chickens dig up. She insists on eating first, using her body to block others from the food bowl. If the other chickens persist, Spicy Mildred will peck them on the top of the head, sometimes drawing blood, and when she starts attacking one chicken, the others will join in. This is not instinct, but a learned behavior. “The other chickens, to stay in her good graces, follow what the leader’s doing,” Castillo-Barrett says. At times, Curry and Blanche Devereaux will hold the bold younger chickens—Peanut Butter and Jelly—back from her.

None of this is obvious to the kids and parents who visit Kiddie Science, because Spicy Mildred is extremely good at her job as an educational chicken. I think of her as a diva, an Elaine Stritch type. She’s the only chicken who can come inside to be observed by kids, and the only one who has learned to be picked up. When she does, she curls her legs in so Castillo-Barrett can hold her like a baby, and she makes happy cooing sounds in her arms.

Castillo-Barrett tells me that all of this—the abrupt change in behavior, the bullying, being antisocial within the flock—is unusual for chickens, though in Spicy Mildred I recognize a common character arc in fiction and history. She came from nothing and worked her way up to Machiavellian leader. She is Imelda Marcos, she is Tony Montana, she is Daenerys Targaryen. She saw her chance to be someone else, to, yes, rule the roost, and she took it. But unlike those figures, she was past her prime egg-laying years when she reinvented herself. She staved off the invisibility of being an older lady, the obsolescence I steel myself for as I enter middle age. For Spicy Mildred, perhaps, it is better to be feared than forgotten.

Now, Spicy Mildred naps a lot. She can’t jump onto a roosting bar, but she’s fast when food comes out. She eats “kibble,” a wet version of the chickens’ regular food, which is easier on her digestive system. If she gets dirt in it and decides she’s done, the other chickens will rush to eat the dirty food; they love it because it’s hers. Her comb has paled and her feet are scaly and dry. Castillo-Barrett trims her nails and massages Vaseline into her feet. Sometimes Spicy Mildred embraces the care, other times she tries to peck at Castillo-Barrett’s forehead. I think of picking my battles with my own kid, of getting caught in the face during a tantrum.

Recently, my daughter came home from school quoting a YouTube video I’d never heard of, something about a singing toilet. Her little-ness is fading. Soon, the things she experiences will be less wholesome than a crotchety old hen, and less knowable. She will speak in indecipherable slang, play songs I’ve never heard. I will try to relate to what she tells me, grateful if she tells me at all. But it feels inevitable that we will drift into our generational silos, her an annoyed youth, me the out-of-touch mother. Though maybe these roles aren’t predetermined. Maybe we can decide who we will be.

I admire Spicy Mildred’s commitment to change. In her, I see the malleability of the self, the infinite possibilities of who you can become, no matter your age. My daughter will continue to be a million new people, and each one may surprise me. I can still change too, if I wanted. I can surprise her.

When a chicken’s time is up, it happens overnight. Her wattle will turn pink or light blue, her feet may look gray. Another chicken will become the boss. When it’s Spicy Mildred’s time, Castillo-Barrett will address the loss with her students through a scientific lens. She and the children will discuss the lifecycle of a chicken, how most backyard hens only live to be seven or eight. They will appreciate what a unique chicken Spicy Mildred is. They will review what they learned from her.

When her friends arrived at Kiddie Science for her birthday party, my daughter first brought them to the turtle’s habitat. “This is Spaghetti!” she exclaimed, in perfect diction.

Katy Hershberger is a writer and editor in New York. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Washington Post, Longreads, Slate, Lit Hub, and elsewhere.

Art by Calli Ryan