Chubby Checker did not write “The Twist.” He did not discover “The Twist”—it was given to him by his mentor, Dick Clark, who plucked him out of South Philadelphia, whose wife gave him his abundantly silly name, and made him a star. Nor was he the first to record it. The first version, performed by the Midnighters—a pre-Motown Detroit vocal group—attracted Clark’s attention when it hit the top 40 in late 1959. Checker is not, surprisingly, a one-hit wonder either, though he sort of is. He had a string of hits in the early 1960s, though most were sequels to “The Twist” or direct knockoffs of it.

But Checker—born Ernest Evans in South Carolina in 1941—is “The Twist” and has been for the last sixty years. It’s a quaint song, built for chaste school dances. The dance is so easy anyone can do it, though that’s the whole point. It didn’t take much, all you had to do was move as if “drying one’s derriere with an imaginary bath towel while pretending to be grinding out a cigarette with one foot,” as described by one contemporary observer. It was also, crucially, a dance that could be done alone. Roy Orbison might have sung for “Only the Lonely” but Checker made a song for them. Checker’s performance is pure teenage innocence and exhilaration—not so different, really, from Jonathan Richman singing about driving along Massachusetts’s back roads with the radio on.

That should be a crowning achievement: In 2008, Billboard magazine, pop music’s statistical Gospel, itself, like Checker himself, a throwback to another era, declared “The Twist” the biggest chart hit of all time, whatever that means. Checker himself would later renounce it as an albatross—an odd but understandable thing to do with the biggest chart hit of all time. “In a way, “The Twist” really ruined my life,” [he said]. I was on my way to becoming a big nightclub performer, and “The Twist” just wiped it out ... It got so out of proportion. No one ever believes I have talent.”

Checker’s invocation of “nightclub performer” is revealing in and of itself. In 1960, Elvis was in the army; Buddy Holly was dead; Chuck Berry had just been arrested under the Mann Act. Rock ‘n’ Roll was dead and the dance craze—and novelty record and, maybe most of all, dance craze/novelty record hybrid—was king. Checker arrived at the perfect, brief moment to put out the biggest record in the country; then, for the next six decades, he wrung it for all it was worth. He was, at the same time, the last celebrity of an older era and the first one of a new one.

***

Asked by the BBC in 1962 what he would do after The Beatles inevitably crashed out, Ringo Starr revealed his secret ambition. “I’ve always fancied having a ladies’ hairdresser’s,” he says as John Lennon audibly chortles in the background. “A string of them in fact!” Ringo wasn’t the only Beatle thinking about a post-mania future—John and Paul McCartney planned on making it as itinerant songwriters; George Harrison vaguely spoke of going into “business”—though he was the only one who had apparently thought about it in detail.

The question of what The Beatles would do after they were famous seems quaint now. They’re The Beatles, for one thing. But now, once you achieve a certain level of fame, you’re famous forever. Maybe you do open a string of ladies’ hairdresser’s but that isn’t your main job. Your main job is being famous—even if you aren’t that famous anymore.

In 1962 it wasn’t like that. The concept of the teen idol was only a few decades old. The idea of being a pop star after age 30 was exceedingly rare. Fame was something that often came fast and left even more quickly. In a few months, the tastes would change; yesterday’s teen idol would become just another schmuck.

Chubby Checker was determined to hold onto his moment and wring it for all it was worth. A talented impressionist, he got on Dick Clark’s radar as a teenager doing impressions of Elvis Presley, the Chipmunks, and his idol Fats Domino. (His first single, “The Class,” featured his impressions of those three singing “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” The impressions are spot on. The song is not.)

It was Clark’s first wife, Barbara Malley, who gave him his stage name. Evans had gotten the nickname “Chubby” from his boss in Philadelphia’s Italian Market; Malley supplied “Checker”, a play on “Fats Domino”. Fats Domino was “big guy” plus “tabletop game.” So is Chubby Checker. It is still perhaps the most derivative moniker in pop music history—it’s also a fitting name for the career that would follow.

In late-1959, Clark heard “The Twist” and knew it would be a hit. He brought it to Checker, who made it one the following year. Sung in the high-pitched, muppet-y voice that would become his signature, it was the song of the summer, then the fall, then the song of 1961 itself. Checker might have cursed the song’s success later, but in the early-60s he wrung it dry. “The Twist” was a huge sensation and Checker was determined to make the most of it. In 1962, with “The Twist” finally fading, he put out a follow-up, the imaginatively titled “Let’s Twist Again”; the same year, he put out a duet with Dee Dee Sharp, “Slow Twistin’” for those for whom the regular “Twist” was too taxing.

He kept putting out dance records. In 1961, he released the album Limbo Party which contained the songs “La La Limbo,” “Mary Ann Limbo,” “Limbo Rock,” and “Banana Boat Limbo Song.” Other Checker hits from the early-60s include a number of attempts at recreating the magic of “The Twist”: “The Hucklebuck,” “The Fly,”, “Dance the Mess Around,” and “Pony Time” were all attempts to start new dance crazes. None of them could compete with “The Twist” or, for that matter, “The Mashed Potato” and other successors. By the following year, Checker would be squeezed out by The Beatles and the coming British invasion (and subsequent rock boom) and Motown.

But he never really went away and instead pioneered a different type of celebrity. Checker may have resented “The Twist” but he became it and refused to relinquish fame, even as it dissipated. He was a kind of proto-modern celebrity, someone who intently held on to his celebrity for decades, even as “The Twist” slowly disappeared. He re-recorded it several times, and released a country version (“The Texas Twist”) and a hip-hop version (featuring the Fat Boys). The various Checker-released “Twist” songs I have encountered include the aforementioned versions, as well as, “Twistin’ USA,” “Twist It Up,” “Twistin’ Around the World,” “Der Twist Beginnt,” “Nothin’ but the Twist,” “Teach me to Twist,” and “The Mexican Hat Twist.” All of these are real.

Checker may have blamed “The Twist” for derailing his “big nightclub career” but he wrung it for every dollar he could and he continues to pop up every now and then, insisting that the song is the biggest of the last century. He has pushed himself into the news cycle in various demeaning ways, protesting outside the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame’s failure to recognize him in 2002. “I’m not doing it to get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at all,” he told The Associated Press in an interview. “I don’t get the airplay that one in my position deserves. ‘Twist and Shout’ gets more airplay than ‘The Twist,’ and that’s not right,” he said. In the same interview he also complained about not getting enough attention for his recent single “Limbo Rock Remixes,” which had just hit number 16 on Billboard’s Hot Dance Singles Sales chart. Ten years later, he was in the headlines again, this time suing a new penis-measuring app called “Chubby Checker.” (Checker settled the lawsuit in 2014, after the app—which cost 99 cents—was downloaded a grand total of 84 times.)

Mostly, though, Chubby Checker has been in the pitch man business for “the Chub.” He has put out a variety of signature foods—”Chocolate Checker Bars, Beef Jerky, Hot Dogs, and Popcorn, all to be washed down with Girl of the World Water (dedicated to his wife),” his website boasts—though only his beef jerky brand, which costs $25 per 4 oz., survives. He sells hats that read, for some reason, “Chubby Checker University” for $50. He still tours, mostly in casinos, although he inexplicably is not on Cameo.

All of this gives him a tragic air: Here is someone who had a fleeting moment of genuine superstardom that he refused to let go. But it also makes him a pioneer. “The Twist” may be a distant memory, but Chubby Checker is still here, selling beef jerky, and singing “come on baby” for the millionth time.

Alex Shepherd is a staff writer at The New Republic.

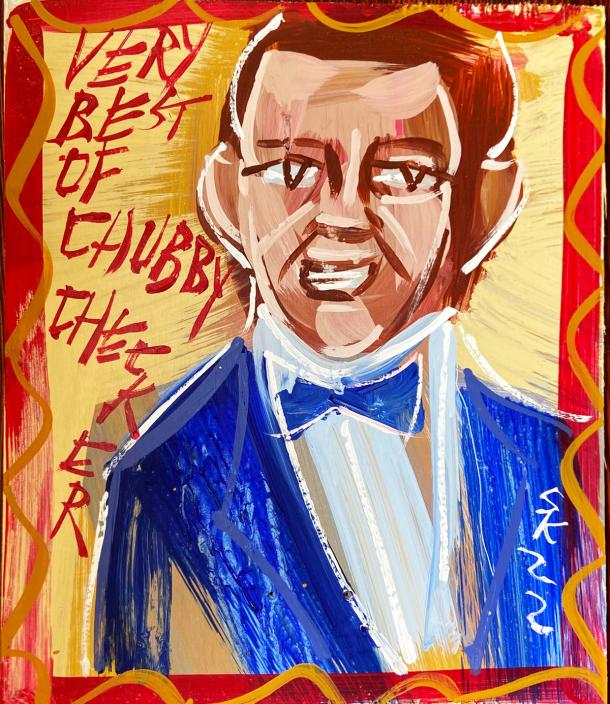

Art by Steve Keene.